Leaping the ‘Valley of Death’: Insights from Harvard’s Workshop on Commercialization Pathways for Fusion Energy

By Alex Higginbottom

The Workshop on Commercialization Pathways for Fusion Energy, organised by Harvard Business School and MIT Sloan School, brought together their engineering and business students with experts in the field of fusion energy.

After a morning filled with detailed technical discussions and visions of the future, hosts Jim Matheson and Josh Krieger sparked a lively lunchtime debate on the 'valley of death'—a phase where technologies falter in the transition from academia to commercialisation. Fusion technology is at this critical juncture, facing a path lined with both excitement and uncertainty.

Here are three key takeaways from the event, and how they factor into navigating the ‘valley of death’.

Key figures in the fusion industry at the Commercialization Pathways for Fusion Energy workshop at Harvard Business School.

1. Communication with local communities, investors, and the public is essential for fusion to succeed.

Nuclear fusion promises abundant clean energy. The goals are admirable, but the implementation is just as important, and communication is key to that.

Heather Jackson, technology to market advisor at the US Department of Energy’s ARPA-E describes the role of fusion companies as satisfying two stakeholders: the first and obvious group is the investors. Clear communication about the benefits, risks, and timescale of fusion is essential for companies to gain the funds they need to actually build the thing – but all of this is essentially academic unless fusion machines can be implemented at scale.

That brings us to the second stakeholder group: the general public, and local communities around fusion facilities. Heather makes the comparison of kid’s vitamins; fusion reactors should be the orange-flavored gummy that communities beg from their parents (in our analogy private investors and government regulators). While the general public may not like their role in this analogy, it carries an important message – the fate of fusion is inescapably at the mercy of public perception. It is the responsibility of both private fusion companies and the public sector to ensure it doesn’t suffer the same disappointing fate as fission.

Community acceptance and support are essential for construction but, beyond that, a lasting, mutually beneficial relationship needs to be fostered too. This means employing a local workforce and maintaining ongoing transparency and accountability. Aditi Verma from the University of Michigan says that “the number one goal is to inform the local populace… engagement should be ongoing.”

Verma advocates visitor centres and ensuring that the local community can understand what is happening in the fusion plant. With fusion energy, we have an opportunity to build a completely new industry with energy justice and inclusivity at its heart.

2. The industry has seen an explosion of new fusion companies – it’s time for the supply chain to catch up.

As of the last Fusion Industry Association (FIA) report, July 2023, there are now 43 private fusion companies all over the world, all with their own fusion concept. Currently, there are a maximum of 3 supply companies explicitly focused on fusion. That’s not going to work.

Tammy Ma, Lead at the IFE Institutional Inititiative highlights this problem: “Energy supply is a $40 trillion industry, and yet there are not enough diodes in the world currently for one device.” (That is the diodes required for an IFE concept such as that proposed by Xcimer Energy or Focused Energy.)

Jennifer Ganten, Chief Global Affairs Officer at Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) emphasised this point, and that CFS is “building supply chain relationships with the view of constructing thousands of reactors.”

When Jennifer says thousands, she’s referring to their self-imposed goal of 10,000 reactors by 2050. To say that represents a supply chain opportunity would be something of an understatement.

As companies grapple with the immense manufacturing and scaling challenges of fusion technology, initiatives like Zap Energy's (represented by AJ Kantor at the workshop) stand out. Their recent acquisition of global capacitor manufacturer ICAR is a strategic effort to secure essential components for advanced power supplies.

While such moves are pivotal, they underscore a broader truth: achieving the vast scales envisioned for fusion energy will ultimately depend on cultivating a large, prosperous external supply chain.

In any mature industry, whether that be car manufacturing or smartphones, outsourcing the production of specialised components is essential for reaching vast scales. As the co-founder of the largest fusion-centered supplier, Kyoto Fusioneering’s Richard Pearson is well-placed to benefit from this momentum. He emphasised the upcoming opportunity, but also that a two-way relationship between fusion companies and suppliers is essential, with “each providing solutions and building up feedback loops.”

Melanie moderating a panel at the Commercialization Pathways for Fusion Energy workshop hosted by Harvard Business School and MIT Sloan School

3. Active and judicious public sector investment is still vital.

The excitement around private fusion companies such as CFS, Zap Energy or Type One Energy cannot be overstated. Private fusion has a real chance to be the first to demonstrate commercially-relevant fusion (such as first electricity on the grid), and they are moving at a rate that public projects like ITER could only dream of. A significant message from the workshop, however, was that despite this fact, private companies can’t do it without public support.

UKAEA’s Tim Bestwick reminded the group that “no large scale energy technology has ever come to market without large scale government support.”

In the past, the public sector has been responsible for facilities such as NIF and JET which have both recently inspired the world with their fusion records. Now, though, it is time for the public sector to move to a supporting role.

The construction of test facilities for various aspects of a fusion reactor represents a critical step forward. These facilities would allow private companies to refine their designs through iteration. Tim advocated for international cooperation to build these complementary systems, highlighting the cost: “These facilities are eye-wateringly expensive…. We are constructing a tritium breeding loop in the UK that we hope to share with the US.”

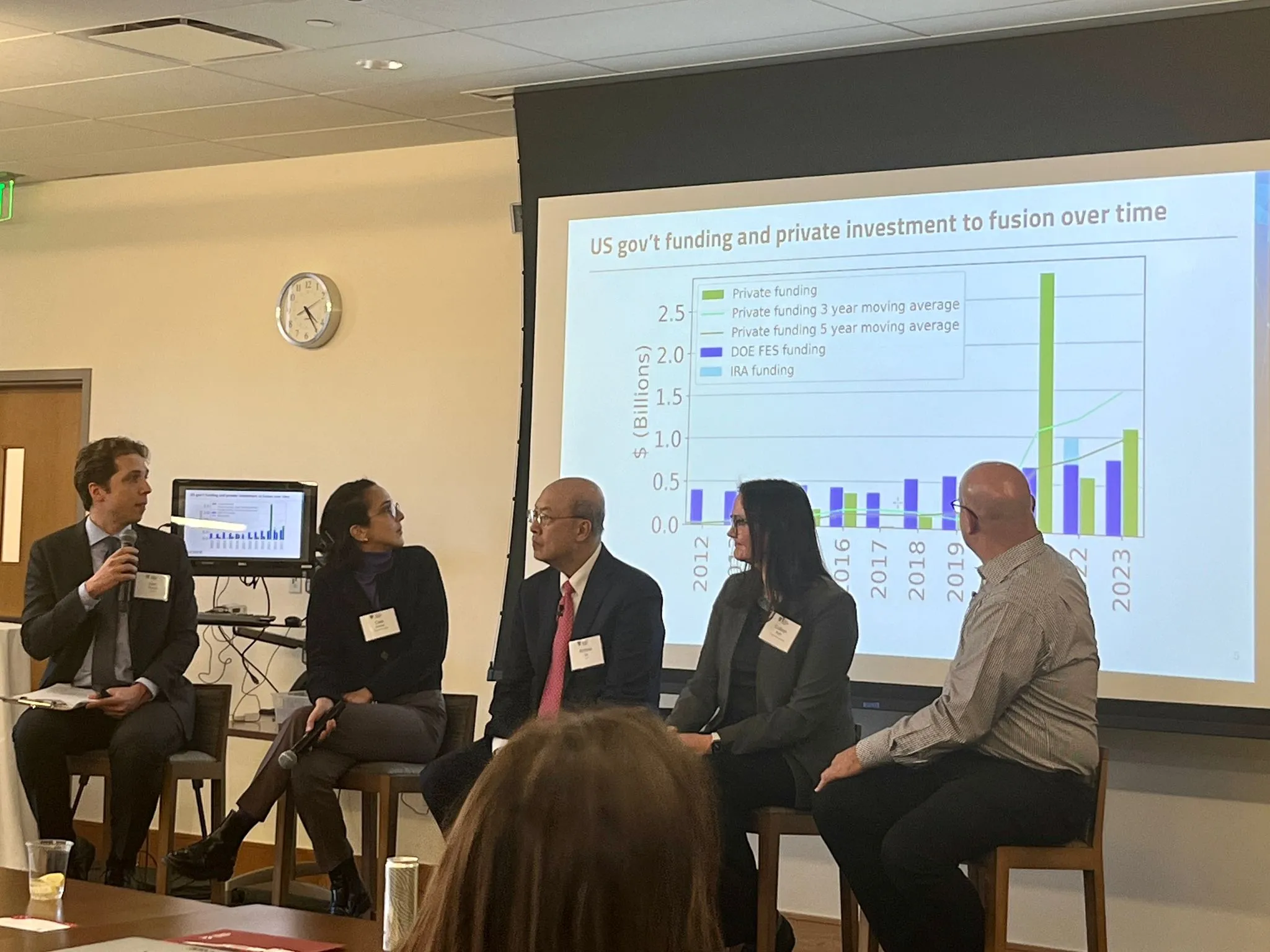

The panel looks at US government investment figures at the Commercialization Pathways for Fusion Energy workshop at Harvard Business School.

This collaborative approach not only helps spread the cost but also enables fusion companies to concentrate on developing their unique nuclear fusion concepts. CFS's Jennifer Ganten reinforced this idea, asking, “How can we divide and conquer?” to distribute the risks and financial needs inherent in fusion development. Fusion is hard enough as it is – let the public sector do the heavy lifting when it comes to the supporting tech.

On the topic of direct investment, Colleen Nehl, program manager at ARPA-E’s Office of Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) described how ARPA-E has shifted from viewing fusion as a ‘blue sky’ high-risk, high-reward investment, to the point where the more fiscally conservative FES has started to engage. There is now a need for public organisations such as ARPA-E to define certain milestones for private companies, that can be independently verified as a way of de-risking, and incentivising, investment.

A final key role, highlighted by Andrew Lo, is the US government’s unique ability to borrow money at low cost (a few percent). “Large private funds are not an option right now, said Lo. “There are no publicly traded fusion companies.”

Lo advocates a $50 billion fund and cites the 10:1 relationship that has been observed in other industries where every $1 invested by the public sector attracts $10 of private investment. “If we create a fusion fund of that type, you will make money in 5 or 10 years.”